Literature review

There are two main ways in which Generative AI might be useful for literature review: it could help to find relevant papers and it could help to summarise papers once you have found them.

Finding literature

When ChatGPT was first released, students who tried to use it for their literature reviews quickly discovered that it frequently hallucinated non-existent references. The model would confidently generate citations with real author names, journal titles, even volume numbers and page ranges—yet when students tried to locate these papers, they simply didn‘t exist. While this has somewhat improved with the latest models, they remain unreliable when it comes to providing references to academic literature.

The new generation of AI assistants, however, can now access the internet and provide links to sources they use to generate their responses. Google Gemini, for example, has a “Deep Research” function, which scans the internet to generate a report on a topic of interest and provides links to all its sources.

It is still not an ideal solution, as “Deep Research” scans the whole internet, not just scientific papers, and apparently cannot access paywalled content. For that reason, when doing literature review, you would probably be better off with specialised tools such as Elicit. Such tools usually have direct access to scientific databases and are specifically designed for researchers to use. You can check out the following video explaining some of Elicit’s capabilities:

I recommend exploring various existing tools, experimenting with them to see how they fit your research workflow and personal style, and selecting the ones that work best for you. At the same time, I would not recommend relying entirely on GenAI for finding academic papers.

Why you should not rely entirely on GenAI for finding papers

The volume of published papers, even in smaller fields, has grown far beyond what any individual can comprehensively read. This means you have to carefully decide which fraction of the literature you want to read, and I think you should be cautious about outsourcing this crucial decision to GenAI tools.

Given that science is a social enterprise, I would definitely recommend prioritising social sources of knowledge. For me personally, this is the main way to discover papers. If a researcher I respect shares a paper on social media and says it‘s worth attention, I trust her judgment and prioritise reading it. When a paper is generating buzz in my research community, I make sure to check it out. I also follow researchers whose previous work I’ve liked, and keep an eye on their new publications.

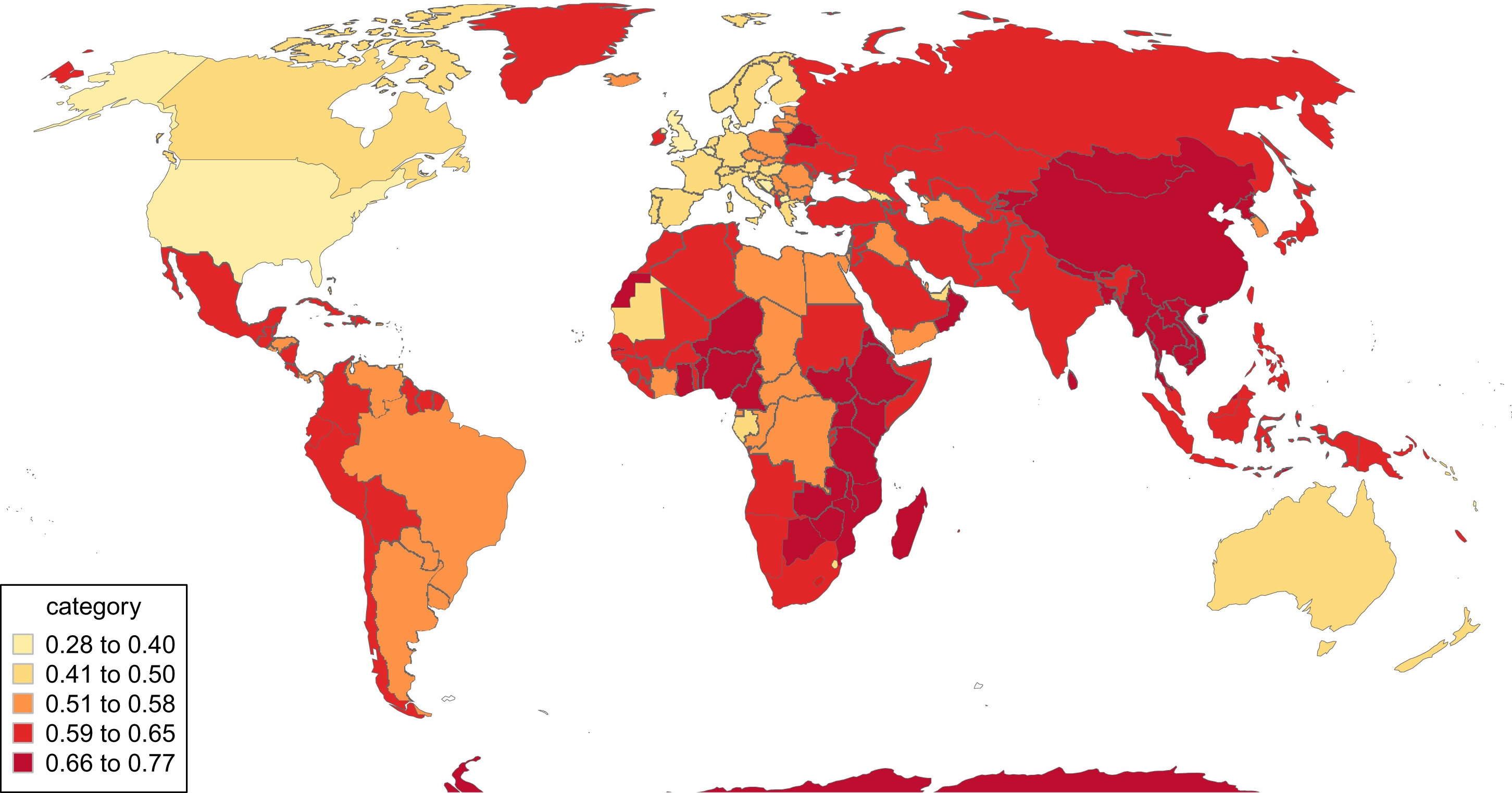

Another consideration is that there are documented biases in scientific publishing. One of them is geographical bias. Both my colleagues and I have encountered situations where reviewers wanted us to specify the country where our data came from—not just in the paper and abstract, but in the title itself. For instance, someone suggested that my paper “Parents mention sons more often than daughters on social media” should be called “Parents mention sons more often than daughters on social media in Russia”. I would be fine with this requirement if it was equally applied to all research. However, there is an interesting paperNorth and South: Naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production (Castro Torres, et al. 2022) showing that there is a significant variation in how often countries are mentioned in paper titles, with the United States being mentioned notably less often than others.

Another bias is that papers in prestigious journals tend to accumulate more citations regardless of their actual qualityJournal Prestige, Publication Bias, and Other Characteristics Associated With Citation of Published Studies in Peer-Reviewed Journals (Callaham et al. 2002) . At the moment, we don‘t know how AI tools interact with these and other biases in scientific publishing—whether they amplify them, create new ones, or potentially help reduce them.

Summarising papers

Similar to hallucinating references, LLMs could also hallucinate summaries disconnected from the actual content of papers. Modern GenAI tools, however, allow you to upload actual documents and ask questions about them, providing direct quotes that you can verify. This makes them very useful for generating summaries or extracting information from text.

But again, I would advise against over-relying on these tools. You cannot learn to write good papers without reading good papers. To really understand a paper and interpret its findings appropriately, you have to carefully check the methodology. Only from full texts, not summaries, can you see how authors frame their results, what limitations they acknowledge, and how they position their work within the broader literature. And you shouldn’t forget that all papers already have a summary in their abstract. The challenge isn‘t usually getting a summary, but rather deciding which papers deserve further attention. GenAI might be useful for summarising information that is not present in the abstract and could help you to make that decision. However, I don’t believe it‘s possible to become a better researcher without reading full papers yourself.

In this course, I reference more than 50 papers. However, I didn’t use GenAI to summarise any of them as it was important to me to check the actual content of the papers. It doesn‘t mean that I’ve read each letter of the papers—being able to scan papers effectively is actually an important skill for a researcher. At the same time, I often went beyond even full-text and checked the actual experimental data shared in supplementary materials. Such deeper dives often revealed crucial details that wouldn’t appear in any summary, AI-generated or not.